Alexi Pappas: Gaining Perspective at Maclaren Marathon

Alexi Pappas reflects on how a change in perspective can refresh your approach to running. Photo: Alexi Pappas

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

For many runners, from professionals to enthusiasts, our sport becomes something to complain about. We moan about the weather, crowded trails, old shoes, aching muscles, past injuries – it’s easy for us to focus on the negatives rather than relish in the positives. It’s only natural. After all, running is a sport that attracts perfectionists – we are always striving to improve ourselves – and it’s our instinct to focus on what we want to change and improve. It’s easy to blame external circumstances for poor performances or bad workouts, but the truth is, for most of us, the only thing limiting our running is ourselves. It just sometimes takes a change in perspective to realize it.

Earlier this spring, I had the opportunity to meet a group of runners who completely refreshed my perspective. For them, running is the ultimate privilege. These runners were inmates at the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility outside of Portland, OR, a prison for boys in their teens and early 20s. For these kids, running is a privilege they earn. Not everyone is allowed to run – it must be earned through good behavior. For those few who earn the privilege, running is a small taste of freedom in an otherwise restricted existence.

Here’s how it works: MacLaren offers rehabilitation programs, from barber training to mechanic classes to journalism courses, and one of those enrichment programs is the opportunity to train for a marathon. The entire marathon is run within the confines of the prison grounds with an interior circumference of a little over a mile. Most runners I know complain about running small loops – I myself have been known to get “tired” of the one-mile Amazon loop in Eugene I’ve come to know so well in my own training – but these young men relish the opportunity. Many of them actually know nothing about running when they sign up, but they do know it is something different and something, presumably, freeing. When they take up the opportunity to run, they learn quickly – in fact, the Eugene Marathon’s own Ian Dobson was a volunteer coach at the program, introducing the inmates to the fundamentals of training and recovery.

Ian was actually coaching me for the 2016 Rio Olympics during the same time that he started volunteering as a coach for the MacLaren marathon program. At the time, my focus was completely on preparing for the Olympics – fine-tuning my performance at the absolute highest level. At that elite level, you’ve got to focus in on “first world problems,” like making sure you’re using the absolute best equipment, training in the ideal conditions, and fueling in just the right way. I remember Ian telling us why he couldn’t be there for some of our weekend training, because he was coaching at MacLaren an hour away in Woodburn, but I didn’t think much more about the program at all. I assumed that all of my energy should be on my own Olympic preparation and I never took the opportunity to go with Ian and help out myself.

But now I understand what Ian got out of his trips up to MacLaren to work with the inmate-athletes: perspective. Transitioning from an environment where elite athletes are paid to run to a situation where kids are grateful for the chance to run circles around a fenced-in yard is a powerful dose of reality. It’s a reminder of why we love to run in the first place.

I experienced this firsthand during my own trip to the MacLaren prison marathon. The running program in the prison culminates in an actual 26.2-mile race around the prison grounds. I was there with a camera crew from Vice, who was creating a short documentary about race day in the prison.

The first thing I did when I arrived was get introduced to the athletes. I expected to meet driven, focused youth, but my expectations were exceeded when I met one kid in particular, Johnathan. I remember the first thing I noticed was the book Johnathan carried under his arm: Mastery, by Robert Greene. This is a book one of my coaches once handed to me and I still reference it today. Johnathan explained to me that one of his fellow MacLaren-mates, a mentor of his, passed the book along to him. He told me about this tradition of some of the boys sharing resources like this, in hopes of passing along the skills and leadership – and hope – that might help them succeed when they re-enter the community. Johnathan and I instantly connected over having similarly profound experiences with this book and I also fundamentally appreciated his desire to be a role model.

Johnathan told me how he spends time training young inmates in the gym as a personal trainer, and then we actually went to the gym together and shared with each other our favorite routines. I felt lucky to learn from him and I am so confident that he will help many people when he re-enters the community.

For Johnathan, this was not his first marathon – he considered himself a “seasoned” marathoner, having competed in the last two editions of the MacLaren marathon program. Out of the other six inmates competing, only one had completed a marathon before. We had a pre-race pasta dinner together which was as surprising to me as it probably was for them. I expected to be surrounded by prerace nerves and anxiety. But what I found was a table full of confidence. For these boys, there was no question as to whether or not they would be able to complete the marathon distance. They expressed to me that compared to the experiences they’d had in their lives, a physical challenge like this – something as simple as running – seemed entirely possible.

Still, the boys looked to me for pre-race advice. So I shared the only tidbit that I thought might be helpful: I told them that I was not necessarily “meant” to make the Olympic team. I told them how I used to be the worst runner on my college team and slowly improved year by year, learning from mentors and teammates around me. Nobody expected me to ever break the top 10 on my team, let alone qualify for the Olympics. I think this was surprising to Johnathan and the others: our circumstance now is not forever. We can take control of our future if we choose.

Then the marathon happened, and Johnathan was the athlete who cheered on everyone around him even when he was in pain. He himself was one of the slower runners, but he eagerly supported when his teammates lapped him. I walked the last five miles with one of the athletes, for whom marathon cramps set in late into the race. While walking, he told me that he will be finished with his sentence and re-enter the community in a few short months. The first thing he wants to do when he leaves: go camping for the first time. For him, running has been the best way to engage with nature while in the facility – something I take for granted when it’s pouring rain and I would rather not go outside to train. The next time I even consider staying inside because the weather isn’t perfect, I’m going to think of Johnathan and get myself out the door.

All of the athletes completed the marathon, even if it meant walking the last five miles with me. Johnathan and the other inmates helped me understand how grateful he was to run – an activity I now understand he sees as a privilege, not a right. I think about running differently now that I have met Johnathan. Johnathan’s goal is to one day compete in the Eugene Marathon and I hope I am there to cheer for him when he does.

During training – whether we’re building up for a 5k or a marathon or the Olympics – it’s easy to fall into a trap of non-gratitude. We focus on the minutiae and obsess with how we can maximize each little bit of our training. But taken too far, this leads to resentment and bitterness. Nothing’s worse than a bitter runner. So every now and then, it’s good to reconnect with what made us love running in the first place. Maybe it doesn’t require a visit to a prison. But seeing those young adults feel free – even as they ran in circles around the prison yard – made an impression I’ll keep with me always. It reminded me to be grateful for every step.

Alexi Pappas: Be a Good Teammate to Yourself

Photo: Alexi Pappas

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

With the track and field championship season coming up, hand-in-hand with final exams for high school and college athletes, it’s important to remember to be as kind to ourselves as we are hard on ourselves.

High school and college are hard enough. Studying for finals, competing in championships, memorizing your lines for the school play – all of these tasks are “hard enough” on their own. We’ve all heard the advice about how to best tackle multiple goals: make a to-do list, stay organized, plan ahead, and so on. But what I’m here to tell you is to remember to be kind to yourself.

What I mean by this is that as you juggle multiple commitments, it’s easy to get overwhelmed and build up stress and resentment, which will decrease efficiency, lead to more stress, and spark a negative feedback loop. But if we can positively manage our feelings and be kind to ourselves no matter how overwhelming our schedules might seem, we’ll be more effective at getting our tasks done and accomplishing everything on our plates this spring.

The first step is to recognize that it is challenging to balance school commitments with athletic commitments. Embrace that it’s hard! It’s okay for things to be hard in life. Recognizing that you have a hard set of tasks ahead can be invigorating and inspiring.

I find that the best way to maintain this perspective is to remember that everything you’re doing is a choice. You’ve chosen to be an athlete. You’ve chosen to be a student. So, during those weeks when you have less free time than your friends who aren’t athletes, just remember that you chose to be in this position.

For me, that’s a very empowering thought: when I’m in the library while my friends are out socializing, I remember that it’s my choice. I’ve seen some teammates feel like they’re victims for being “stuck” in the library. But that’s a negative perspective – they’re forgetting about the bigger picture. The bigger picture is that they’ve made a choice to be student-athletes, and there are only 24 hours in a day, so of course they’re here in the library when their non-athlete friends aren’t. With that perspective, being in the library becomes a pleasure. It’s something you’re doing to earn your life as a student-athlete, just as much as showing up to practice and working out. Getting into this positive headspace of choice rather than sacrifice is the most important step towards being kind to yourself. I specifically recall one midterm exam period at Dartmouth when a bunch of my cross country teammates and I decided to post up on a Friday night in the otherwise empty library. We chose to do this together and even though it wasn’t a party in the traditional sense, it felt like a party to us.

The next step is to take a close look at the hours in your day and determine if you’re using them well. I think of my time in 30-minute intervals, usually just enough time to get one small task done, and it amazes me how many “intervals” I discover in my day when I’m thoughtful and disciplined. Instead of checking my phone while I’m sitting on the bus, I’ll open my computer and get some work done. If I’m feeling worn down and I need a break, maybe I’ll spend that 30-minute interval on social media instead of getting work done, but usually if I’m being honest with myself I know that ultimately I’ll feel better using my spare “intervals” to cross things off my to-do list. I like to treat the time intervals the same way that I’d treat an interval of running: once I commit, I’m in it until the interval is over. This makes it easier to focus when I’m working and it also makes it easier to let go and relax when I’m not.

Another strategy I use is to determine exactly what I have to do and what I don’t. This doesn’t mean that I skip things, but it does mean that I try to work smart. I prioritize my tasks, and usually the first line of defense is saying “no” to opportunities that take up time in the day that aren’t directly related to my immediate goals. For a student, this might mean turning down social opportunities during championship season, or dialing back involvement in other clubs just for the few weeks of spring competition. Or it might even mean asking your teachers if you can work ahead on your academic syllabus so that your workload is lighter during competition time. It also means taking the time to figure out how you study most efficiently. Some people work better in groups, others make study guides, and so on – the point is that it’s sometimes easy to slip into working how it seems we “should” be working even if that isn’t the most efficient way for you personally.

I understand that all of these suggestions actually seem like more work at first, but really it’s just being proactive so that when competition season comes you’re not suddenly faced with work and commitments that could have been handled in a more efficient way. Even though it takes a bit of willpower to plan ahead and work smart, I see this as being kind to myself because at the end of the day, I know that I’ll sleep better and feel more relaxed if I know I used my time well.

And that is my ultimate self-kindness test: whenever I’m faced with a decision about how to use my time, I ask myself: “will doing X help me fall asleep easier tonight?” Some days, vegging out on social media or going out with friends really is the answer. But most days, making the choice to get ahead of my to-do list is the kindest choice for me.

Being as kind to yourself as you are hard on yourself takes practice. It’s a different mindset than most of us are accustomed to. Because being kind to yourself doesn’t mean letting yourself off the hook – it’s just the opposite. It means that you’re having intention with your day and looking out for your best interests; it means that you’re your own teammate. Teammates hold us accountable, teammates believe in each other, and teammates always want the best for each other. This spring, be a good teammate to yourself.

Alexi Pappas: On the Benefits of Racing Below Peak Fitness

Alexi Pappas racing amongst her competitors at the Pacific Pursuit 10k. Photo: Alexi Pappas

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

After racing the 2018 Chicago Marathon, I was proud that I had made major strides since my injury a year earlier, but I also knew that I had a ways to go before I would be ready to qualify for Tokyo 2020.

Building up my fitness meant toeing the line at races I knew I wouldn’t win. I don’t like losing, but racing is a very motivational training tool for me, so skipping out on races until I was “fit enough” wasn’t an option. So after Chicago, my coach and I signed me up for a track race in early February: a 10k in San Diego, where the competitors would be chasing the world standard time. Technically, I had the fastest personal best going into the race by about 40 seconds, but my coach told me honestly that I was “not in Rio shape.” In the past I might have avoided toeing the line in such a situation, fearing losing to women I felt I should beat. But the truth is, I knew signing up for this race was the right thing to do.

Why do we sign up for races in the first place? One, a race on the calendar gives us a certain period of time to commit to, a time during which we are focused on the one goal coming up. Two, upcoming races make us nervous in the good way. Thinking about a race is like thinking about Christmas – you know it is coming and you do everything you can to prepare. You think about your outfit, the meal beforehand, and you can hardly even sleep the night before. But that’s okay because it’s Christmas! Three, competing in a race provides an honest assessment of where you are in terms of fitness and readiness, both physically and mentally. It always provides some kind of honest feedback from which to move forward.

When I ran the 10k in San Diego, I was feeling good. I wanted to celebrate my health and run as hard as my fitness would allow. When the race began I put myself in the front pack, running a pace my coach already told me might be too fast for me to sustain for the entire race. The top few women in the race had just qualified for the World Cross Country team, so they knew they were in good shape. I understood this intellectually, but when the race actually started I didn’t have the heart to reign myself in. I wanted to stick with these girls, who I believed I could beat at my peak, but who were now far fitter than I was.

About 5k into the race, I hit a wall. Thankfully it was not an injury wall, but instead it was a fitness wall. My pace dropped off and I finished the race far behind the lead girls. Coach put it this way: I was 100% healthy and 60% fit.

I was happy, of course, to be healthy. That was the whole point of this race, to test my fitness and confirm my health after the Chicago Marathon. But I still couldn’t help feeling sad at not running faster. “Bravies” were coming up to me to take photos, and even though I was smiling on the outside, on the inside my mind was racing. I was wondering how long it would take me to get fit, if I’d ever get fit again, and have other great runners gone through this?

I gravitated towards one of the women I just raced – Jen Rhines. She is a three-time Olympian and someone I’ve long admired. “What would Jen do?” is a common refrain amongst her teammates and really anyone who has been lucky enough to train with her. That’s because Jen is known to have an even mind, a long career, and the right balance of grit and wisdom. She is a good example for anyone. I met Jen in Mammoth Lakes, Calif., when we were both training at altitude and have admired her ever since.

I worked up the courage to ask Jen: “Have you ever had a race like this? A race where you didn’t run as fast as your peers because you’re not super fit, but you know or hope you’ll get there?”

Jen nodded immediately: YES! She had been there, exactly in my position, and completely understood and empathized with what I was feeling. She was never afraid to put herself on the line and has had her fair share of races like this. I was so grateful and relieved to hear that from her. It would be one thing to hear this from my coach or my dad or anyone else, but hearing it from Jen, who had literally been in my shoes before, meant the world to me. This is what we can offer each other as peers in this running world: we can share our specific experiences with each other, which will help add to the greater understanding of what a running journey can look like. For me to know that Jen had been in my position before gave me permission to believe that it was an okay and even necessary and good part of the process. She made me feel capable. I left the track feeling optimistic and energized instead of sad and scared.

When I was younger, I would have never put myself in a position to race when I wasn’t ready to run my best. But now I understand the diverse functions that racing can have in an athlete’s career. There are races, like the Olympic Trials or the Olympics, when we should show up 100% ready to race. And then there are other races, less high-stakes ones, which help us practice a specific tactic, and then there are others that are meant to show us where we are. I remember going to a race on the Oregon Coast where I was just meant to practice my prerace routine. Then I ran another race where the goal was to work on my finishing kick. This race in San Diego was meant to kick my butt and pump me up for the season ahead.

It is glamorous to show up for a race when you are ready to compete for the win, and it takes grit and bravery to show up when you’re not. It’s better to confront your limits and get your butt kicked than to avoid them. There is a time and a place to race conservatively, and this wasn’t one of those times. That wasn’t the purpose of this race. That being said, it wasn’t easy losing to women I would rather beat. It wasn’t easy running slower than I am theoretically capable of. But it was the truth.

I heard a story about a world-class athlete who had an injury that took her out of competition for a very long time. Luckily she got healthy and her coach was ready to throw her back into competition. But there’s a huge difference between being healthy and being fit. That’s what’s so hard about being injured: you work so hard to fix your injury only to have to work hard again to claw your way up back to your peak fitness, all the while avoiding getting re-injured.

So this nameless athlete, she was finally healthy again, but she refused to show up to races because she said she “wasn’t ready.” Meaning, she was too afraid to lose. She did not want to race and lose to girls she would have beaten before her injury – she wanted to first regain her fitness, thenrace. But here’s the thing: you will never be “ready.” It takes racing – and losing – to regain your fitness and return to the competitive level you were at pre-injury. When you put walls in front of yourself because you’re afraid, you might find that you are never ready. The fear of racing and the possibility of losing became so large that she was never able to race … her career fizzled out and she never competed at the highest level again.

It takes bravery to race because racing is not about always being ready. The point is that we show up, then show up again, then keep showing up until we finally achieve our goal. When you win or run a personal best, that’s fantastic. But when you don’t, you still benefit. You’ve still committed to something and followed through. You’ve gained experience, you’ve gained fitness, and you’ve gained pride. That’s what racing is all about.

Alexi Pappas: Good Idea to Embrace Invisible Tradeoffs

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

A family member passed away recently and I needed to fly to the east coast with two days notice for the funeral. This is tough news for anybody, but for an athlete, traveling is doubly challenging: when your job is your body, intensive travel takes on a whole new level of costs. I needed to get from remote Mammoth Lakes in California to the east coast, which is not easy in the middle of winter.

For an athlete, traveling doesn’t just mean you’re sleepy the next day, it can potentially throw your entire training cycle off balance, and possibly even lead to injury. Runners love routine – I’ve written about this before. But sometimes, immediate circumstances come up which override all else.

I needed to be there.

Naturally, the upcoming journey felt stressful. I was sad for my family’s loss. As an athlete, I had two training runs and a long run on my original training schedule which I’d now need to somehow figure out how to fit in. To make matters worse, my flight out of Mammoth was delayed and the airline rebooked me on a redeye. I didn’t sleep at all and only had one hour from when I arrived on the east coast until I needed to leave with my family for the funeral. Since I landed feeling quite sleep-deprived, I decided to take the day off. I think most runners in my position would have made a similar choice. In my mind, one day off wasn’t a big deal. I would still make it back home to do my long run the next day.

The weather, however, had other plans. Due to high winds, my return flight back to Mammoth was re-routed to San Francisco. Instead of being at home with my teammates, I was stuck in an airport hotel in an industrial area until the next day. As icing on this terrible cake, it was pouring rain and howling wind and the hotel treadmills were all broken. It was one challenge after another.

Still, I thought, I couldn’t skip my long run – especially since I hadn’t run the day before. I didn’t want to start out my week with a huge mileage deficit. So I laced up my shoes and braved the crazy storm outside along the industrial road.

Within minutes I knew this run was a bad idea. I was in the hurt box, bad. I could feel the exhaustion from the weekend, both emotional and physical, down to my bones. Each step felt like a struggle. Now look – I’ve had tough runs before, and I know that sometimes you just need to suck it up and push through. I’m not one to shy away from hard work. But deep down, I knew that this wasn’t one of those moments. I knew this from experience. Because through my experience as an athlete over the years, I’ve come up with the concept of “invisible tradeoffs.”

An invisible tradeoff is when you need to sacrifice your training for the greater good because of a reason that might not have been intentional at first. In my case, it was not my intention that my weekend would be as exhausting and stressful as it was. Because here’s the thing: your cells know EFFORT. When your body is tired it needs to recover, period. Even though a sleepless night on an airplane will not result in the same athletic benefits as a long run, your body’s need for recovery is the same. If you ignore the invisible tradeoff and try to have both things – the exhausting weekend and the long run – you are taking a serious risk of injury.

Luckily, as the windswept rain crashed into my face, I saw two high school-aged boys merrily trotting along the path ahead of me. They were wrestlers trying to lose weight before a big match. I asked if they were from around here and if I could run with them. And since I was trying too hard to run fast on my own, I knew that going with these boys would not only feel safer, it would be smarter for my body because it would force me to run their pace: in this case, high school wrestler slow.

I tucked in behind them and just ran whatever they were doing, which ended up being much less mileage at a far slower pace. I felt bad for a moment that I was running so slowly, but then I reminded myself of the tradeoff I was making and put the run into perspective.

I made it back to my hotel and promptly passed out until my flight the next morning. The following week, I had one of the best training weeks of my life, including a mile repeats workout that I will never forget. Had I over-trained and under-rested the weekend before – ignored the invisible tradeoff of the travel and stress – I probably would have had a mediocre training week at best, and an injury at worst.

Here’s the thing about invisible tradeoffs: we need to accept that they are real, legitimate things that demand recovery just as much as any training. I imagine that many stress fractures and other over-training injuries could be avoided if more coaches and athletes took invisible tradeoffs into account. As athletes, we either need to have the maturity to accept these changes in plans, or at the very least, tell ourselves: let’s not and say we did!

Alexi Pappas: On the Importance of Dynamic Movement

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

I never knew quite how important dynamic movement was to my health as a runner until after my first major injury when I had to regain all my fitness from scratch. For me, “dynamic movement” refers to exercises that force my body to move and gain strength in non-running ways – specifically, side-to-side and up-and-down movements that don’t strengthen naturally with running alone. While dynamic movement doesn’t directly make you a faster runner, high dynamic strength can be a helpful factor on an uneven cross country course or in a rough track race, and most importantly, having a dynamically strong body increases durability and prevents injuries.

When I was developing as a runner in high school, dynamic movement was a major part of my training, but I just didn’t know it. Competitive soccer (and recreational basketball and other sports) were an integral part of my life until college – what I knew was that it made me happy, what I didn’t know was that playing other sports made me a much stronger and more durable runner.

In soccer, for example, as compared to running, movement is much more lateral and unpredictable. Movement happens in all directions, including sometimes up in the air, and a goal in training is to prepare your body to jump, slide, switch directions, or execute any number of other movements quickly and efficiently. So naturally, the training included more lateral, dynamic, and jumping type movements as compared to my cross country and track training which was much more straightforward (no pun intended).

When I went to Dartmouth, I carried over much of the durability soccer lent me into my collegiate running life. I believe my athleticism sustained throughout my first few years at Dartmouth and likely even beyond, since I did not get any injuries. Perhaps my participation in intramural hockey my freshman year played some role, but in any case, I still felt like an athlete. I went to Oregon for a 5th year and we were trained in dynamic movements by legendary coach Jimmy Radcliffe. Our running coach, Maurica Powell, worked to incorporate Coach Radcliffe’s training into our routines, and many of the movements we did reminded me of what I might have done as a soccer player. I did not feel particularly graceful when doing those routines, but I knew that small doses of athleticism continued to be infused into my training and would benefit me tremendously.

My dynamic athleticism continued into my professional career, where my coaches continued to have us jump, throw, push, and more at practice (outside of our running), but ultimately I got my first serious injury at age 27 shortly after the 2016 Rio Olympics. This injury happened after a series of sudden stresses that I encountered at once, and mainly boiled down to over-training and under-resting as I transitioned into becoming a marathoner. The injury took me out of running for nearly six months. It took me months to find the right kind of care to help my specific injury, and by the time I did, I was completely out of shape. I tried to maintain my fitness through cross-training, but we didn’t want to push my body and exacerbate my injuries through overdoing the cross-training. So, the result was that I not only lost my running fitness, but also the athletic dynamic movement durability that I had built up.

In time, I became healthy and was able to run and train again. Then, just as I was beginning to taste fitness again, I got re-injured. I recovered, started running little by little, and got injured again. I didn’t understand why I was caught in this cycle. What was I missing?

Then I sat down with my physio, John Ball, and his team at Maximum Mobility Chiropractic in Arizona, and discovered the issue. Instead of just looking at my injury in the moment, John traced me back to my athletic roots. When I first found running and started to get really good, I was coming to the sport as an athlete. I was already playing soccer, basketball, and softball – and this athletic background provided the foundation for my transition into running. As I was running more and getting faster, I was doing it with an athletic body that had a built-in durability. Now, here I was trying to come to running from zero. It was like I was trying to paint a wall without putting the primer down first. None of the paint could stick. I understood that as I worked to slowly regain my running fitness, I also needed to work on regaining my athleticism. I needed to jump, leap, and move sideways. I needed to incorporate dynamic movement into my training.

Only this time, I would do it right. Instead of racing to reach 100 miles a week, I ran 4-5 miles a day and took high intensity interval training classes to help me become the durable athlete I needed to be. I dedicated time each day to working on my dynamic movement, pulling together my favorite exercises and drills into a “circuit” every day. At first, I almost did more dynamic movement work than running. Then, in time, I was able to incorporate more and more running. I started to recognize myself again – I started to feel the connection between my body and mind that I was familiar with, but hadn’t felt in a long time. Now, I run more miles than I do explosive jumps, but I will never completely phase out athletic movement in my training routine. Just yesterday, I picked up a basketball and dribbled it around the gym after weights practice, and I knew it was a good sign when I still felt somewhat natural going for a layup.

As a special addition to this story, I wanted to share more specifics about the dynamic movement “circuits” I created for myself. The inspiration for my circuits came from Dr. John Ball, Coach Jimmy Radcliffe’s book, and Sarah Whipple, a former UO teammate and a High Intensity Interval Training designer.

You do not need to do a circuit every day. They should be incorporated into your weekly plan as it makes sense, perhaps only doing circuits on easier running days. As your mileage increases, perhaps one circuit a week or on an off day is the best plan to avoid overtraining.

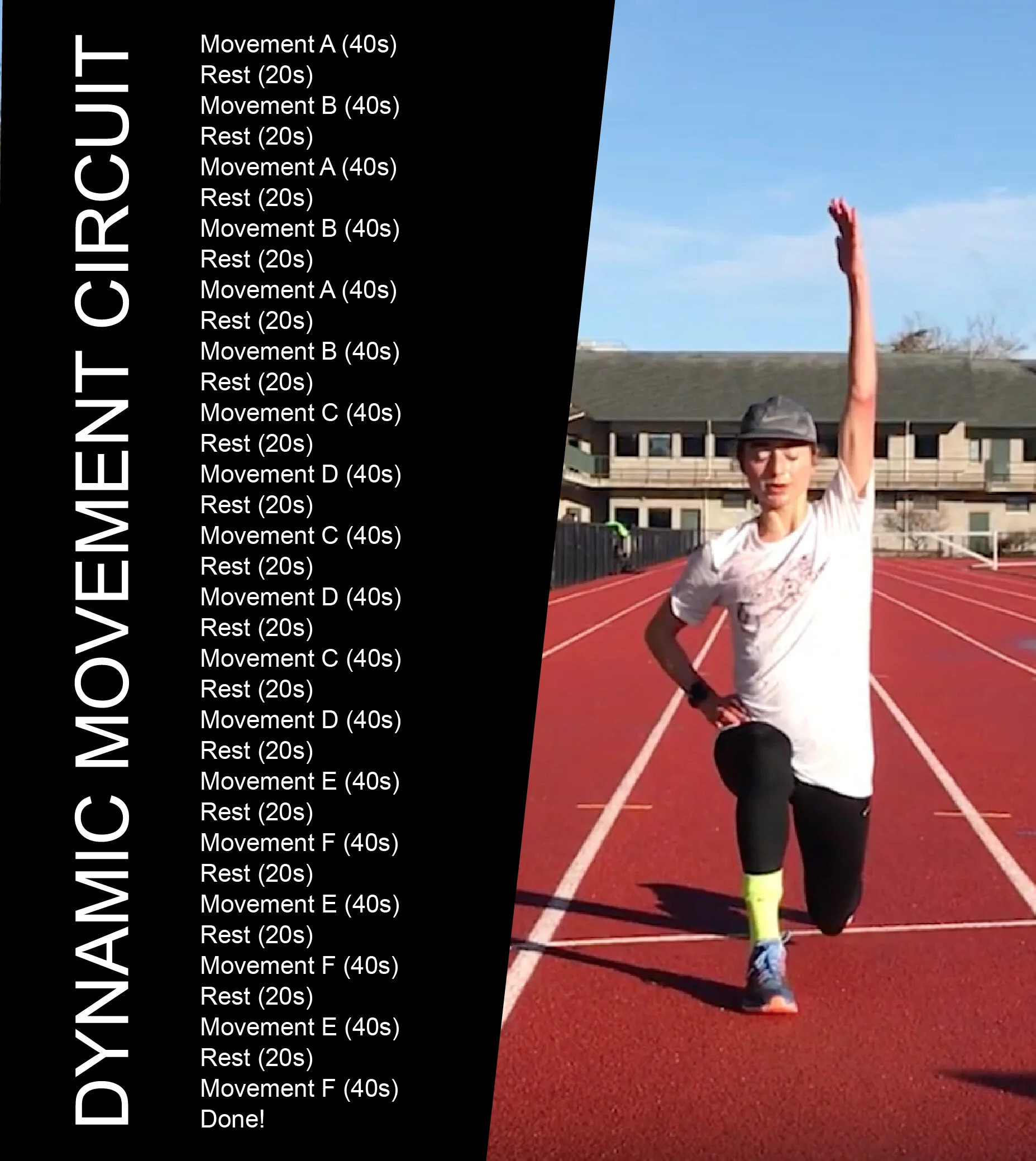

Now let’s get to the specifics. In total, one “circuit” takes me about 18 minutes. The 18 minutes are broken down into three 6-minute sets, each comprised of two different movements which I alternate back and forth (for a total of six movements). I like to do 40 seconds “on” followed by 20 seconds of rest, rotating between two different movements three times each. So the entire circuit looks like this:

In terms of what each of the four “movements” are, I follow these general guidelines: 1) something sideways, 2) something vertical, 3) something core, and 4) something where you “explode.”

Some specific examples: a speed ladder is great for the “sideways” circuit, step-ups on a low block work well for vertical, deadbugs are great for core, and med ball 180 turns are great for the “explosion” movement.

There are unlimited resources online for dynamic movement ideas, and it’s up to you to categorize them and build your own circuits. I like to switch it up – I never do the same circuit twice! This is important, since the whole point of dynamic movement is to constantly change things up and keep your body guessing. I have a trove of dozens of movements that I mix and match when I design my circuits.

Alexi Pappas: Why I Love Turkey Trots

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

I was introduced to the tradition of running “Turkey Trots” later in life. At first, the idea of running a race on Thanksgiving morning did not excite me: I’ve always been resistant to running on holidays, especially the one where I am meant to eat, take a nap, and then eat again. But now I’m hooked on the Turkey Trot tradition and it has become an indispensable part of what I look forward to when I think of Thanksgiving.

I ran my first Turkey Trot in the fall of 2016, shortly after the Rio Olympics. This was a large Turkey Trot with an entire field of elite athletes. But there was also an open race with hundreds of people, and I convinced my husband, dad, and best friend to sign up. After the elite race finished, I joined my family in the crowded open field. It was wonderful. We were surrounded by people, some serious and some running in turkey costumes, and the atmosphere was festive and playful. When my husband stopped to walk, I walked with him. It was so different from the sometimes stressful world of “serious” racing. It was a nice reminder that racing is FUN. After the race we drove back home and had our Thanksgiving feast, buzzing with the energy of having just run a race together. It was a bonding experience. I loved it.

When I reflect back on why I loved my Turkey Trot experience so much, I realized that it came down to a sharing of joy. First, fun-running in the open race with my loved ones reminded me of my love of running and the running community. Without the pressure to perform and run fast, I was able to enjoy all the little things that make running such a special group sport. Rather than zoom past the spectators and volunteers along the course, I could slow down – or even stop – to give a high-five and have a connection. I ran with my phone, snapping selfies along the way. I had a blast. And the next time I toed the line at a competitive road race that would have otherwise been nerve-wracking, instead I was reminded of all the FUN things associated with road racing and it brought a smile to my face.

But the joy isn’t one-way. I believe that by running in the Turkey Trot together, my loved ones also gained a deeper appreciation for the sport I love so much. Often, when my husband or dad is at a race, they’re there to watch and support me. They enjoy being there, don’t get me wrong, but frankly it can be a bit stressful. They know that I have professional and personal stakes in the race, so there’s a competitive anxiety in the air, which can be exciting but also not super joyful. And also, they are on the sidelines. Like many family members who come to support us runners, our loved ones are not able to run at the level we are. So when they come to a race to support us, they exist on the outside. But when we all run the Turkey Trot, stopping for walk-breaks as needed and just having fun, we are all in it together. They get to experience the joy of participating in a race themselves, no matter what their pace. And that personal experience of joy stays with them, helps them have a deeper appreciation for the sport, and ultimately brings them closer to you. In a sport that can so often feel isolating and individual, especially at the highest level, this kind of inclusion can be so important! It fuels your whole team. And when your team is strong, cohesive, and positive, that fuels you as an athlete.

For those of you still skeptical about taking the Turkey Trot plunge, I get it. I was once like you. But here are eight reasons why I love Turkey Trots and why I think you will too:

Everyone can participate together. My dad semi-walked it, my husband raced against my best friend, and I raced against elite runners when we all ran the Silicon Valley Turkey Trot. It was amazing to all toe the line together.

You can stay local. Most towns host their own Turkey Trots. There are large ones, and smaller ones, and they all feel like a community gathering.

It’s a holiday, so the atmosphere is festive! The thing about a Turkey Trot is that everyone’s there to have FUN. Sometimes road races can get intense, but that tends not to happen on a Turkey Trot. People are there to cheer and celebrate and get pumped up for dinner!

It’s short. Most turkey trots are short enough that there’s a race in there, but you’re still going to have energy for the rest of the holiday – maybe even more energy after that runner’s high! It’s the perfect amount of challenge to give you and your family that nice sense of accomplishment.

It’s genuinely healthy to move around before you feast. In fact, you might find that you enjoy your Turkey Day meal even more after that burst of excitement from your morning Turkey Trot. Don’t be shy about luxuriating in a post-meal nap – you’ll have earned it.

The weather can be awesome. It’s nice to have an excuse to get outside and spend time in the fall before winter sets in.

Race shirt with a turkey on it: I have so many race shirts, but one of my favorites is my Turkey Trot shirt because … it’s silly! It has an adorable turkey on it. Plus, if your whole family participates, then you all get to look super cool in your matching shirts.

So, if you’re on the fence, just give it a try – and I promise that you’ll have a good time, and maybe even discover a new tradition that you’ll look forward to for years to come.

Alexi Pappas: Lessons Learned from my First Marathon

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

Since I ran my first race, a 5k fun run attached to a larger marathon in Napa, Calif., I have understood the marathon to be the most classic distance race. I remember watching my dad cross and collapse across the finish line of the marathon later that day with a time of just over 4 hours, and I remember how proud but tired he looked.

When I had the honor of sitting in the lead car for the New York City Marathon, I had the chance to see thousands of people cheering for loved ones alongside the course. I saw the leaders finish, and then, hours later after a dinner party at Tavern on the Green, I returned to the finish line and saw the very last runner complete her race with a small crew of marathon employees cheering her on. I had considered racing a marathon last year and even two years ago, but decided to wait until the moment felt right – and this year at the Chicago Marathon, I decided the time was right to finally brave this epic event myself.

The 2018 Chicago Marathon was my first serious race since the 10,000 meters at the 2016 Rio Olympics (I’m not counting the 5k Turkey Trot I ran in November 2016, which was literally the last time I stepped up to a starting line). I took significant time away from competition to deal with the first big injury of my life, and also to give myself some time to transition to marathon training. My training cycle building up for Chicago had gone very well, but my coach made sure I was aware of what the specific goal of this marathon was: to race, of course, but most importantly, to gain an understanding of the marathon itself. Mentors had told me that the marathon could be considered its own sport entirely different than track. But until I experienced it myself, I couldn’t quite fathom what this truly meant.

Before the race, I spent time visualizing the race and imagining parts where I thought I might struggle. I imagined myself pushing through the rough patches and continuing on. I visualized myself executing the race plan I developed with my coach. I imagined myself excelling in this new event. I even spoke to young athletes at an event in Chicago a few days before the race about this very concept: about how if you visualize yourself not giving up then you are more likely to succeed. But no amount of visualizing could have possibly prepared me to truly understand what I was about to endure.

“I TOED THE START LINE LIKE GOOD PASTA: SLIGHTLY UNDERCOOKED. MAYBE TOO UNDERCOOKED, BUT THAT IS ALWAYS BETTER THAN OVERCOOKED.” – ALEXI PAPPAS

I toed the start line like good pasta: slightly undercooked. Maybe too undercooked, but that is always better than overcooked. I felt the same pang of excited nervousness that I missed so much during my time off from racing. I was at the very front of the start line, with thousands of people behind me all about to wrestle the same monumental task together. I thought for a moment about how running is a team sport masked as an individual sport. Then the gun went off, and we went.

The first unexpected thing I noticed was my GPS watch didn’t work properly amongst all the other GPS-clad runners and tall buildings. I would need to split my watch manually and try to run by feel – but for me, coming off such a long break, running 5:45 per mile pace wasn’t as intuitive as it used to be. I hadn’t run consistently at that pace so often, especially because my training was done at high altitude (8,000 feet), where we generally train much slower. But I stayed calm and tucked into a pack. I found a group of men to run with, but quickly found that, like me, they were also having trouble sticking to one pace. Then it began to rain! I felt excited and grateful to be racing, but increasingly overwhelmed by what became a much more complicated race.

Then, about 10 miles into the race, I began to feel a weakness in my leg that had previously been injured. My hamstring was tugging and I felt my mobility decrease with each passing mile. The feeling wasn’t pain, more of a limitation, but it was unexpected and restrictive nonetheless. I’ve experienced moments of pain before in races, where it was up to me to push through, but this was different. It wasn’t a matter of pain, it was a matter of mechanical limitation. Apparently, though I was healthy in every other way, my hamstring was not yet strong enough to carry me at those paces for a marathon distance. This limitation had never revealed itself in practice, but now – at a distance beyond anything I’d ever raced before – I was forced to deal with a challenge I had not anticipated or prepared for at all.

Inside, I had a moment of realization where I understood I was not going to physically be able to achieve the goal I had set for myself. It was not about mentally pushing myself to do it – I’m no stranger to pain but I literally could not run faster than I was running. But that didn’t mean I needed to stop. I could feel that my hamstring could keep going, just not anywhere near the pace I planned. I had a choice: clock a time I wasn’t hoping for and perhaps finish in a place that could be seen as embarrassing, or drop out. Some elite runners will drop out of a race so that they don’t finish with a “bad” time on their record. This is the easy way out. I thought about how I might feel ashamed to finish a race with a performance that is beneath what I am capable of and what people expect from me. What would be the worse failure: running slow or dropping out? Does crossing the line but not achieving your race plan mean you are a failure? Or is it better to stop so you can never know for sure how you would have finished? There is a lot of time in a marathon to think.

Alexi Pappas running the 2018 Chicago Marathon. (Photo: Alexi Pappas)

But then I opened my ears to the voices around me. All around me, people were cheering for me, yelling “go bravey!” I let those voices flood my mind for a mile or two and felt the sudden understanding that although I was no longer able to achieve my initial goal, I could still accomplish a goal. I could change my goal mid-race and redefine what success meant for me in this race. I changed my goal to simply focusing on finishing the race.

My goal was no longer to race the marathon but to finish it. Simply continuing to put one leg in front of the other became the ultimate challenge for me. I felt a sudden calmness – I felt that I was suddenly folding into the thousands of people behind who all had the very same goal. The Chicago Marathon is many people’s first marathon, and I imagined I was not the only one who would be beyond proud to finish the thing.

Every runner who passed me cheered for me, and I no longer felt ashamed. I felt grateful for their support, because it actually felt real. I felt like I was experiencing the world in slow motion. The race was long, so very long. But sure enough, 16 miles turned to 17, 18 to 19 … and so on. I focused on things outside of myself: the crowds, the city of Chicago, and the teens I’d told nights before that if chasing a goal were easy, anyone would do it. I told them I’d been the worst on my team before, which was the case when I first went to college. I worked my way up slowly. I understood at mile 22 that the marathon might feel the same way. I have always been a late bloomer and nothing has ever come easy for me. But when I hang in there, things do come. I know the marathon is like that too.

I will never forget the feeling when I saw the finish line. Alongside the finishing straightaway were all the people I loved: my family, my husband, my coach, my team, and even my best friend since I was two years old. I felt overwhelmingly proud because I knew I accomplished my goal. I also felt a twinge of sadness that I had to let go of my initial goals – but I knew that was because of a factor beyond my control – my hamstring – and I had no choice.

That’s the tricky thing: determining when you should re-frame your goal versus when you need to dig deep and double down on it. You control what you can control, and you can’t control what you can’t control. For example, it started pouring down rain in the middle of the race – another uncontrollable factor. If that had been the only uncontrollable thing to happen to me, I still would have needed to adjust my goal to account for the slower pace due to rain. The things you can control – pain, determination, fueling – those are factors that, ideally, should never cause you to re-frame your goal. Those are things you work hard to perfect and conquer. These challenges are characteristic of all the races I’ve ever run. I’ve always had to make choices to not give up. But how do you know the difference between reframing your goals versus giving up?

Alexi Pappas and Jeremy Teicher catch up post-marathon. (Photo: Alexi Pappas)

It is incredibly important for us as athletes to understand the difference so that we can properly assess our decisions during a race and maintain our integrity to our goals. The most important thing as athletes is to have integrity with our goals: which simply means that we always want to try our best. If trying our best is compromised by things within our control, this is a problem, but if our best is compromised by things out of our control, then doing our best simply means performing to the best of our ability within the new limitations. So even if your goal changes – your pace is slower due to rain – your integrity is still maintained.

At the Chicago Marathon, I was fighting two limitations that were totally out of my control: the rain and, more urgently, my hamstring. In this situation, trying my best meant reframing my goal. I still felt sad about not being capable of achieving what I set out to do, but I was happy I had integrity as an athlete nonetheless. And what made this experience particularly special to me was that I was not alone in this endeavor. In the Chicago Marathon, there were thousands of people all trying to do the same thing: to run with integrity. I sensed that as I was pushing myself, so was everyone else around me at the very same time. I understood that this experience connected me not only to the runners around me, but also to all marathoners who have ever crossed the finish line.

Alexi Pappas: A Good Coach will Help You Love Your Sport

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

Running is a sport where the athletes are driven by love: at some point along our athletic journeys, we fell in love with the sport. This love can strike at any stage in life, but for many of us, it was first sparked by a coach – sometimes later in life, but often in high school.

It is not always our choice what coach we might have in high school, but the lucky ones get someone who is selfless, energetic, and thoughtful. A great coach, I observe, turns “I” into “We” and gives athletes permission to believe in themselves.

My high school experience was quite different. When I was in high school, I didn’t love running. The coaches at my high school (at the time) were insistent on everyone on the team focusing solely on running – this may be a good idea for a college athlete or an aspiring Olympian, but I was only 16 years old when I was asked to quit all other activities and just run. And while I was a very talented runner, one of the best in California as a sophomore, I wasn’t in love with the sport yet. I enjoyed winning and I enjoyed running as one of the many activities I did at the time: soccer, theater, student government – activities I loved because of the leadership I found in coaches and mentors there. I was not ready to quit soccer, student government or theater.

A 16-year-old should never be asked to quit anything. A 16-year-old should be encouraged to do all the things that will stretch her mind into believing in itself. And so, I got kicked off my high school team by coaches who simply didn’t understand this. I didn’t run my junior and senior years of high school. My high school coach had a hugely negative impact on my impression of running. It would have been very easy for me to never run again.

But my life changed when I got a phone call from the first coach who helped me understand what running can be at its best: her name was Maribel Souther and she became not only a coach but a mentor and a maternal figure for me as I moved across the country to pursue running at Dartmouth. The first thing Maribel did was to bring my new teammates and me to the woods of New Hampshire to engage in a training camp where there was no tap water or electricity. There, we had no distractions besides the sound of our footsteps in the woods. There, I understood that running could be a team sport and that it was okay to love running and also be good at running. At the time, I was the worst on my team and also in the Ivy League and probably one of the worst D1 runners in the country. I was not good enough to travel and compete with the team. However, that did not mean I couldn’t love it. Maribel took us adventuring through the woods and allowed me to understand how to amuse in pain alongside teammates who truly wanted me to be by their side. I improved slowly but surely. Being good, I learned, would come with loving what I was doing. And loving what I was doing took being around other people, and most importantly a leader, who loved what they were doing.

Maribel retired from coaching when I was entering my junior year, and this was when I was lucky to meet another incredible coach in my life: Mark Coogan. Where Maribel essentially introduced me to running in a way I hope people get to be introduced when they are much younger, Mark brought me into the mental side of the sport and showed me what believing in myself really meant. Mark is himself an Olympian, and so his confidence in me meant a lot. It was more impactful for me to hear Mark tell me it was okay to set lofty goals than when my dad told me the very same thing. This is the benefit of having a coach who has “been there,” as Mark has. It’s a different sort of mentorship than your parents can ever provide. Mark picked up where Maribel left off and helped me understand that my love for running could translate seamlessly into my commitment to my goals in running and, ultimately, success beyond my wildest dreams. I may not have been ready to take this kind of step as a 16-year-old, but when I met Mark, I was 20 and ready. Mark gave me permission to believe in myself in a way that has left a permanent impact on me. I have not stopped believing in myself.

When I had the chance to go to Oregon for a fifth year to be coached by the incredible Maurica Powell, I took it. Maurica is a rare person in that she is able to be extremely focused on coaching at the highest level one moment, and then switch gears and show us how to have a flourishing personal life outside the sport. Yes, Maurica elevated me as a nationally competitive and NCAA Championship team member athlete, but she also showed my team and me what it was to be a successful woman with a thriving career and vital family life. There were times when Maurica told us when she had stayed up late because her son was sick, and there were also times when she didn’t tell us anything about her personal life because it was Championship week. In total, she knew how to help us develop as athletes who could win national titles and also as people who can envision their life after college, and for that I am very grateful. Maurica knew that in order to be a successful athlete, you need to feel that you are thriving. This is a word that she uniquely used, and it continues to be a guidepost for any life decision I make today: “will this choice make me thrive more or less?” This guidepost applies to everything from training decisions to non-athletic choices – a thriving life needs to be balanced, and that balance is different for everyone. This was the perfect lesson to learn as I transitioned into a professional running career.

As a professional, I’ve had the gift of being coached by Mark Rowland, Ian Dobson, and Andrew Kastor, who helped me become the Olympian I am. Coaching in the pro world feels similar but different from coaches in the academic world: you become more of a partner with your coach, two professionals chasing the same goal. But the same general principles still apply: a good coach will always make you believe in yourself and encourage you to have a thriving life … and above all, a good coach helps you understand how to love the sport.

Alexi Pappas: Nothing Routine about Summer Training

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

My college coach once told me that a solid fall season is made in the summer. At the time, this didn’t make sense to me, but now I understand that summer is the time to rejuvenate, prepare, and grow in a different way than is possible during the school year. Over the summer, we grow on our own terms.

So what does it actually look like to transition from the team season and school year to the summer time when we must fend for ourselves? The biggest change is in the routine. Routine is very important for a runner. Whether it’s daily team practice, adult running groups, or even just a morning run, committing to a routine is key to achieving athletic goals. So, as we enter summertime, when our established routines are put on hold – school is out, work gives way to vacation – it’s more important than ever to keep long-term goals in mind and proactively create new routines to stay on track.

Of course, it’s not always possible or even ideal to maintain the exact same routine in the summer as you did all year – but it is important to create a new routine that will work for your changing schedule. If your team does not meet for practice in the summer, or if you’re traveling and physically not in your usual place, you’ll have to plan ahead. Rather than suddenly find yourself off-balance in a new situation, it’s so important to expect and embrace this time and create a new routine. What I find is that if I don’t plan ahead and find myself in a new place or situation without a routine, it takes extra willpower to adjust and create a new routine on the fly, and my training takes a hit as a result.

The summer after my freshman year at Dartmouth I had my first full-time real job at a green start-up in Oakland, and I needed to learn how to train at a time other than my usual Dartmouth team schedule of early afternoon. I tried training in the morning but found that my sleep was too precious, so I adjusted to evening runs. I also found that I needed to run a few less miles to account for all the energy I put into that job. I always like to think about how my cells don’t know mileage, they know energy output—and I needed to adjust accordingly.

So, in order to proactively create your new routine, the first and most important step to a great summer is to determine what your goals are. It’s always important to know what your goals are, running or otherwise, so that you know what you’re working towards. Goals give us something to wake up for. Your goal could be preparing for a specific race, it could be to stay consistent and healthy, or you could be looking to build a strong base for a successful cross country season in the fall. Write your goals down so that no matter where summer brings you, you always know what your athletic trajectory will ideally be.

The second step is to anticipate the changes that you’ll be facing this summer and how that might impact the pursuit of your goals. Will your team stop meeting regularly? Do you have a vacation booked? Will you work full time? And so on.

The third step is to determine what new routines you’d like to establish to best achieve your summer goal. It’s also good to take a look inward and decide what you will need to thrive. If you love the regularity and accountability of team runs but your team is off for the summer, then communicate with like-minded runners and form your own group schedule together. If you know you’ll be in a new place, do the research ahead of time and locate the best running trails near where you’ll be staying. You could even reach out to local running groups and ask to temporarily fold in with them. Overall, the more you can plan ahead of time the easier it will be to get out the door each morning – you’re “checking a box” every day rather than reinventing the wheel each morning.

As you embark on your new routine, it’s very helpful to keep in touch with your teammates or running partners throughout the summer to remind you of your goals and to encourage you to be accountable. I never pushed to be in touch as much as I would during the school year, but it’s always great to have someone to check in with and feel a sense of satellite support. My class of girls on the Dartmouth cross country team had an email chain we used to keep in touch and share photos from our very different summers. I liked knowing that even though we were all somewhere different, we were also all preparing to reunite again.

I also find that it’s very helpful to continue calling training “practice,” even if you’re meeting just yourself and the birds! I set a specific time to get out the door each morning (or evening) so that I made sure I do it, just like I would if I had my coach waiting for me. This is also the advice I share with someone who is not on a team but who has a goal – anyone with a running goal might call their daily trainings their “practice.”

Also, remember to sleep! The school and work year can make it tough to find time to nap or get nine hours of sleep each night. The summer is a perfect time to sleep diligently, recharge, and convert all the hard work you did over the past year into growth.

The last thought I’d like to leave you with is to embrace the change that summer brings and enjoy it! Yes, we runners are creatures of habit, but shaking up our normal routines can be incredibly positive for our long-term growth. It can be sad to leave the teammates you love, but take advantage of the opportunity to explore running on your own or with new people.

One summer when I was away from Dartmouth, I met and trained with a group of women who changed my running life. I was living in Los Angeles and I reached out to an all-adult-working-women group of runners called the “Janes,” and they showed me that running truly is a choice and our time training is meant to be relished. These women helped push me way out of my routine in a good way, as I’d wake up at 5:30 a.m. to meet them at some far away pier and chase the sun up into the sky as I listened to stories so different than those I’d hear from my college teammates.

So, if you’re traveling somewhere new, embrace the change. Running is the best way to discover a new place. Find new trails! Get lost! Make new running friends! Make this summer an adventure! Some of my favorite running memories are from when I’m exploring a new place and falling in love with new trails.

One summer, my teammate Greta Feldman and I decided last minute to go train in Park City, Utah, together, and every day felt like a new adventure as we discovered trails we never knew existed. When I went on family vacation to Paris in high school, I saw more of the city than anyone in my family because I ran outside every morning before our tourist activities began.

So just remember: as you identify your goals, anticipate the changes to your normal routine, and proactively prepare your new routines, remember to have fun and embrace this summer as an opportunity to grow.

Alexi Pappas: Olympic Runner Shares Pre-Race Tips For Eugene Marathon

(Photo: Josh Phillips/TrackTown USA)

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

With the glory of the 122nd Boston Marathon behind us, many of you might be thinking about running a marathon yourselves. Or, with the 12th Eugene Marathon just around the corner, hopefully many of you reading this article are just days away from toeing the line in Tracktown, USA! What the Eugene-Springfield community has to offer in the world of marathon running is very special – whether you’re from the area or not, the Eugene Marathon is an amazing way to celebrate the place where running was born. This is where I feel I grew up as an Olympic runner, and where so people find their “place” as a runner.

I haven’t run a marathon myself yet but I have run countless major road races, paced the Chicago Marathon twice, run a leg in a marathon relay, and I’ve also had the honor of riding in the lead car at the New York Marathon and being the ceremonial starter at a few more. So, whether your big race day is coming up in Eugene (April 28-29) or is sometime on the horizon, I wanted to share some invaluable pre-race tips that I’ve picked up along my career ahead of your big day.

1) Know your plan for race morning ahead of time. If you plan to use the shuttles or bag-check or if you purchased race-day packet pickup, make sure you know where those things are before race day! On race day, you want to conserve all your willpower and energy for the actual event – you don’t want to worry about where to park or where the shuttle pickup is or any other details like that. Remember that there will be dozens, hundreds, or thousands of people just like you all showing up to the starting line – give yourself ample time and anticipate logistical challenges ahead of time. Troubleshooting logistics ahead of time is just as important as any run or workout you can do leading up to the race.

2) Preview the course. Some marathons, including the Eugene Marathon, host “preview runs” ahead of race day. But even if the event doesn’t have any official previews, I still recommend driving the course or at least carefully studying the map as much as possible. It’s important to see the twist and turns and small rises and dips of the course! I do this before every road race, taking careful notes, and then I visualize the night before so that I know what to expect. I find that this helps me control what I can control during the race – having the knowledge to expect certain turns, hills, and aid stations leaves mental space for the unexpected and things we can’t control.

3) Practice your fluid intake during your long runs so that when you see the fluids offered along the course, your body will be familiar with taking in fluids and you’ll be familiar with the practice of drinking while running. Since the Eugene Marathon is right around the corner, take the time this week to practice drinking during your early week runs – even if it’s a short run, it’s so great to understand the way it feels to grab a cup of water or electrolytes and familiarize your body and hands with this process! When I watched the NYC Marathon from the lead car, I could tell which athletes were practiced “drinkers” and which were not.

4) Control what you CAN control, which is everything except the weather. Familiarize yourself with the course, with your routine on race day morning, lay out what you’re going to wear the night before, something tried and true. I have certain routines I never stray from: for example, my prerace meal. During all other times in the year I am very adventurous with my eating, but before a race I rely on the same meal every time. My go-to is some combination of chicken, bread, almond butter, avocado, and sweet potatoes.

5) Find a mantra: I like to tell myself to “stay” during every single race I run. I find that deciding on a mantra ahead of my race helps me return to something positive during moments in the race where I might not feel so great. Finding a mantra may sound silly, but on the chaos of race day, I find that it calms me down and lifts me up. I repeat my mantra on the start line before the gun goes off, so that it’s the last “gift” I give myself before the race begins.

6) Be thoughtful about your friends and families ahead of time. Make arrangements with family and friends at least two days in advance so that the day before you’re just relaxed and enjoying your rest day. It’s best to avoid wrangling with where your loved ones are going to be cheering from when you’re trying to focus on the race. Of course, it is an amazing feeling when you do see a loved one along the course! It can feel as wonderful as a sip of well-needed electrolytes. So find out where they will be cheering well ahead of the race.

7) Remember that it hurts for everyone. This is something I think about especially during longer races, where everyone encounters rough patches at some point – I used to think maybe I was the only one hurting, but then I realized racing hurts for everyone. This was both comforting and motivating. When you realize everyone is pushing through a challenge together, it distracts you from your own pain and also pushes you to continue alongside your peers.

8) Soak it in. Relish in the community of fellow runners. One of the things I love about road races is the gift of the environment around me – always changing, always interested. Especially during the Eugene Marathon, there will be so many sights to take in: the trees, the unique houses, the diehard running fans who keep the spirit of TrackTown USA alive and thriving.

9) From time to time, think about the finish line in Historic Hayward Field, and think about your contribution to its unique history. You’re a part of something special, and you’re also adding to something special when you cross that finish line. I have always heard that a marathon is a celebration of fitness and goals, and I love that. I love thinking about a race as something you’ve decided to commit to and earned. I will always remember watching my dad cross the finish line of his first (and only) marathon – I hope one day I will fully understand why he was crying!

10) And when you’re finished: respect your achievement. You’ve just completed a marathon!! Make sure to relish in what you’ve accomplished. This means going out and enjoying the rest of what the Eugene-Springfield community has to offer. After my track races at Hayward Field, I like to go out for pizza or a burger. And then I rest. Make sure to recover properly before diving back into training for the next one!

Alexi Pappas: What a Summer Olympian Learned From Winter Olympic Athletes

(Photo: Alexi Pappas)

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

When I competed in my first Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in the summer of 2016, it was exactly that: a first. I had only competed in an international competition twice in my life before, and never on a stage as big as the Olympics.

In Rio, I was razor focused on my 10,000-meter track race. I wanted to run a personal best and break a national record. I wanted to finish in the top half of the best in the world. Thanks to my focus and my training, I accomplished all of these goals.

My days were structured. In the days leading up to my Olympic race, I did the exact same thing each day: slept in, woke up, ate, trained, went to the gym to stretch, ice bathed, ate, napped, trained again, ate again, and slept. I noticed and amused in the whole experience, but I tried not to get too involved in anything social – so, yes, I loved seeing athletes celebrating in the Athlete Village pool outside my building each night, but I closed the curtains before 10 p.m. so I could sleep.

In Rio, I was more of an observer. In Korea – as a member of the new Olympic Artist in Residence program – I became outgoing. For my film, I asked athletes to be themselves in short, improvised scenes with either myself or my co-star, Nick Kroll. What this meant is that I met and spent quality time with so many different athletes! For one scene, I wandered into the Athlete Village game room and sat next to a “skeleton” athlete from Jamaica.

He explained to me (my character) all about how in skeleton (riding a small sled down a frozen track while lying face down), you use a steering technique that is much like the children’s song, “head, shoulders, knees, and toes,” – meaning, steer with your head first, and only use the toes for emergency. I loved learning directly from athletes about techniques like this, because it allowed me to appreciate the challenges and goals of each sport. I’m not quite brave enough to throw myself down an ice track head first, but I do appreciate that all Olympic athletes can relate to one another.

I also met a snowboard halfpipe athlete from Ireland, who told me he hopes to become a pilot once he’s done competing as an Olympian because it’s the best way for him to continue “flying.” My heart melted in the good way as I learned that all of us Olympians do what we do because we love how it makes us feel. In running, I love how I am using my whole mind and body to propel myself forward. I like how simple running is. I like how I can improve by putting in time and effort.

My most memorable conversation was with Team USA gold medalist Jamie Anderson, who has an interaction with my character in the free hair salon available to athletes in the Village. We talk about success, but we also talk about failure – and there’s where it got interesting. My character Penelope (and me in real life) is always so curious about how someone like Jamie approaches rejection and failure. She’s experienced it, of course, but that’s not always the most outward-facing side of a gold medalist. I look forward to sharing her perspective with the world through my films, a perspective I found to be refreshing and positive. Jamie is truly an example of positivity, resilience, and also groundedness – she encourages my character Penelope to enjoy the Games. They are, after all, a once (or maybe twice!) in a lifetime experience.

I spoke with a freestyle mogul skier, Morgan Schild, about the differences between a sport where judges determine the winners and sports like running and cross-country skiing where the athletes are directly competing against each other. Morgan told me that her competitors feel like they’re all on one big team against the judges, and whether they win or lose isn’t entirely up to them. Running, of course, is completely different. I knew that there were judge-based sports in Rio, but I never got the opportunity to really hang out with any synchronized swimmers or divers – I was too focused on my own competition!

My character in this film – I play Penelope, a cross-country skier – was inspired by a few real-life cross country athletes: namely, my college friend, Erika Flowers, and 2018 gold medalist Jessie Diggins. My character wears glitter just like Jessie! I spent time researching and chatting with cross-country ski friends to learn about their sport so that I could portray my character Penelope from a place of truth. It is so important to me that people like Erika and Jessie are proud of what I put on screen.

I now have a much deeper appreciation for the Olympics than ever before. I wouldn’t have thought that was possible after my experience competing in Rio, but now that I’ve had a chance to peek “behind the curtain” and learn more about the countless moving pieces that come together to create the Games, I am even more acutely aware of the immense passion, creativity and dedication that goes into each Olympics. As an artist, I felt lucky to truthfully capture the experience of competing and being at an Olympic Games, and feel that this project will make my fellow athletes very proud.

Alexi Pappas: On Going to the Olympics as an Artist

(Photo: Alexi Pappas)

By Alexi Pappas / TrackTown USA

This February, I went to the Olympics in South Korea – not as an athlete, but as an artist. I was selected for the new Olympic Artist In Residence program, an effort by the IOC to reconnect athletics with the arts. Historically, the Olympics have had a strong tie to the arts and this Artist in Residence program, which started in Rio 2016, reignited this once strong tie.

As an athlete and artist, it has always been of the upmost importance that my athletics and my arts stand on their own—that is, I wanted to qualify and compete in the Olympics on the merits of my athletic ability, and I also wanted to make an award-winning movie that traveled to festivals and was distributed worldwide. I feel strongly that these worlds enhance each other, but they should never lean too strongly on one another. When I received the invitation to the Olympic Artist in Residence project, I saw it as a moment where my two worlds fully intertwined: I was on their radar because of my performance in Rio, and I actually got the call because my film was good enough to catch the eye of IOC President Thomas Bach.

For my project, I traveled to PyeongChang with my partner Jeremy to write, direct, and star in a series of short films. It’s been nearly two years since my own Olympic experience where I broke a national record in the 10,000 meters for Team Greece, and I still feel like I have yet to fully express how being an Olympian felt to me. I realize that every Olympian’s experience is wholly unique, but I also think there is a joint emotional experience that every Olympic athlete can relate to—this is what I wanted to express through my films in PyeongChang.

Why make a film? When I sit in a movie theater I feel like I am experiencing something personal and individual, but also completely together with a group of people. That’s how the Olympics felt, too – all of us athletes were there to compete against each other and win medals, but we were also going through a shared experience together. Film felt like the perfect corollary to my Olympic experience.

Like my movie Tracktown, filmed right here in Eugene, my goal was to make a film that athletes will want to show their children to say: “this is what it felt like to actually be there.” I remember the moment 2012 Olympian Bridget Franek said these exact words to me after watching Tracktown, and how much that meant to me. I also remember when Nick Symmonds told me that he related to Tracktown’s protagonist Plumb — he was one of the very first people to read our script, and his kind words gave me confidence that the story really was able to speak to a shared athletic experience.

Tracktown was unique because it was a fictional film that spoke to my true experiences as an elite athlete and Olympic hopeful. When it comes to the Olympics, fictional film is different from watching television coverage or documentary programs on the Olympics. With fiction, we can “zoom in” on specific moments – especially moments between competitions – and capture emotions and experiences that might get overlooked on TV or in a documentary.

With this philosophy in mind, Jeremy and I set out to make a series of short fictional films capturing the Olympic Values through narrative storytelling. We also released behind-the-scenes “making of” videos on the Olympics Instagram account while we were filming.